Long Life Then and Now:

Why Ancient China Turned to Yangsheng

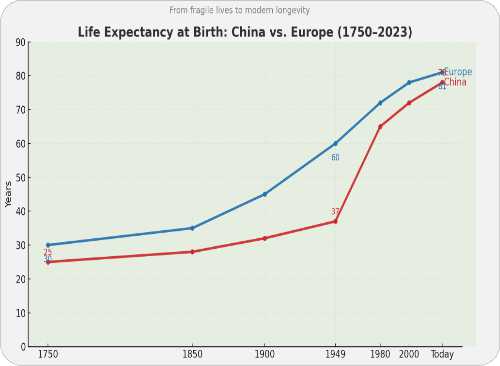

When we think about health today, it is easy to assume that people in ancient times lived in much the same way, only without modern medicine. The reality is more striking. Historical records show that life expectancy in China (and in Europe) just a few centuries ago was far shorter than it is today. That difference helps explain why Chinese culture placed such great emphasis on yangsheng (养生)—the art of nourishing life.

In Qing dynasty registers from the 1700s and 1800s, the average life expectancy at birth was often less than 25 years. Even among the nobility, who had better food and shelter, the average still hovered in the thirties. The main reason was high infant and child mortality. Many babies did not survive their first years, and epidemics or famines could sweep away whole families. Yet if a person lived to age ten, he or she might expect another 35 to 40 years of life, reaching into the forties or fifties. Longevity, in other words, was possible—but never guaranteed.

Fast forward to the mid-20th century. In 1949, at the founding of the People’s Republic of China, life expectancy at birth was still only about 35 to 40 years. Within three decades it had nearly doubled to 65 years, thanks to improvements in sanitation, public health, and basic medical care. Today, the average lifespan in China is around 78 years, a figure once unimaginable. The shift is one of the most dramatic improvements in human health recorded anywhere.

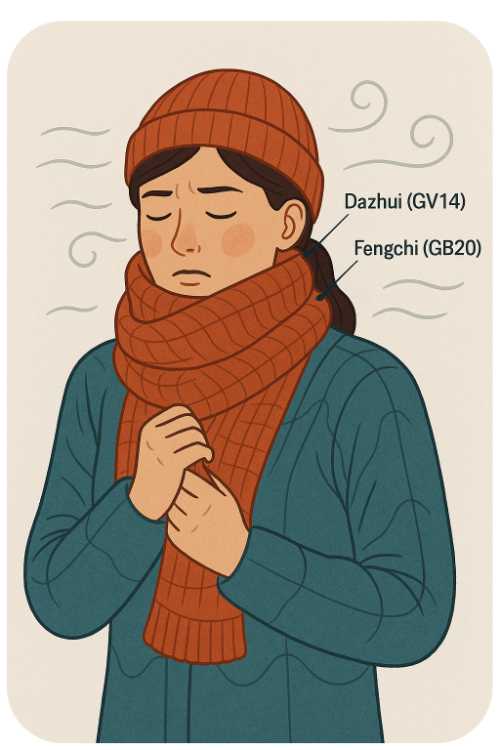

Seen against this backdrop, the cultural role of yangsheng becomes clearer. In a world where disease, malnutrition, and uncertainty shaped daily life, people sought practices that could protect and extend their fragile existence. Daoist breathing exercises, Taijiquan, Qigong, herbal tonics, and dietary guidance were all part of this search for balance and resilience. Confucian thought emphasized moderation and duty, while Buddhism taught detachment from suffering—together forming a rich fabric of ideas about how to live well even when life was short.

Seen against this backdrop, the cultural role of yangsheng becomes clearer. In a world where disease, malnutrition, and uncertainty shaped daily life, people sought practices that could protect and extend their fragile existence. Daoist breathing exercises, Taijiquan, Qigong, herbal tonics, and dietary guidance were all part of this search for balance and resilience. Confucian thought emphasized moderation and duty, while Buddhism taught detachment from suffering—together forming a rich fabric of ideas about how to live well even when life was short.

The fascination with immortality in Daoist tradition also makes more sense in this context. When so many lives were cut short by forces beyond control, the dream of transcending death was powerful. Yet even when immortality remained out of reach, the everyday methods of yangsheng offered real tools for maintaining health, preventing illness, and enjoying a fuller life.

Today we live in a very different world. Vaccines, antibiotics, and modern nutrition have made average lifespans far longer. But the principles of yangsheng still speak to us. They remind us that length of life is not the only measure... quality of life matters just as much. Practices like mindful movement, seasonal eating, and cultivating inner stillness can enrich our extra decades with vitality and peace.

The story of life expectancy in China is therefore more than numbers. It is a reminder of how fragile life once was, and how deeply that fragility shaped culture. The traditions of yangsheng are not simply ancient curiosities; they are living practices born from the human desire to make the most of whatever years we are given.